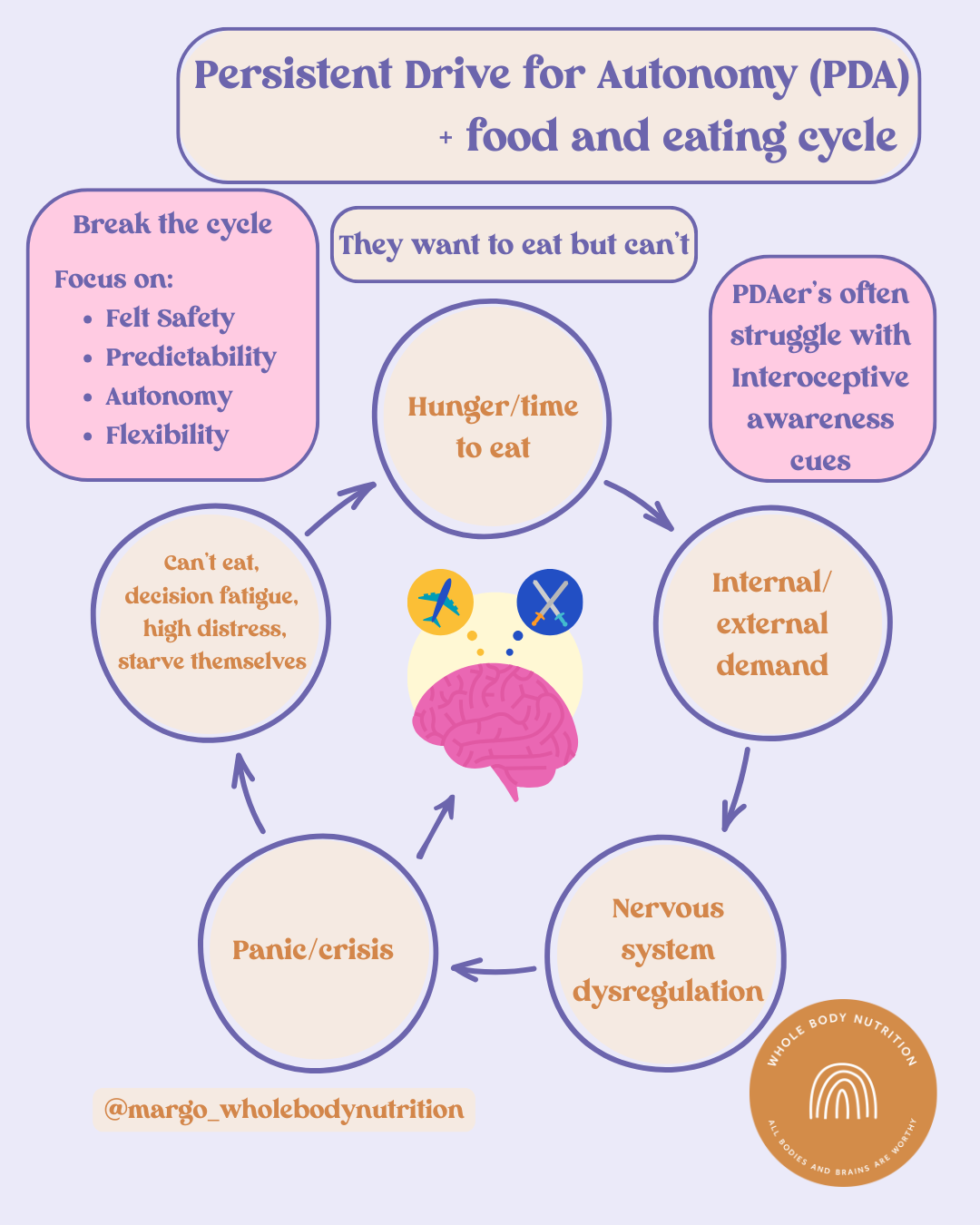

The Persistent Drive for Autonomy (PDA) food and eating cycle

Interoception can greatly impact eating for PDA individuals. It can impact appetite, hunger, thirst and feelings of fullness.

For many PDAers, eating can be experienced as a perceived threat, and paradoxically, the greater the hunger, the harder it becomes to eat. Hunger itself may show up as an internal demand, something the body is insisting on, and internal demands can be just as triggering as external ones. What others interpret as a simple bodily cue can feel overwhelming, intrusive, or even frightening.

Often, hunger isn’t recognised until it reaches an urgent or crisis point. By the time the body signals “I need food,” the internal distress may already be so high that eating becomes nearly impossible. This can lead to a cycle of panic, shutdown, or avoidance, reinforcing the idea that eating is unsafe or too demanding.

The brain becomes caught in a painful conflict: the biological need to eat for survival versus the nervous system’s perception that eating is unsafe due to heightened threat responses, discomfort, or loss of autonomy. When these systems collide, eating stops being a straightforward task and instead becomes an incredibly difficult and complex experience layered with fear, overwhelm, and urgency.

To break the cycle:

This is a gradual, gentle process that requires patience, understanding, and compassion. The goal is to create an environment where the nervous system can settle, cues can be interpreted more accurately, and the individual can begin to recognise what safety feels like in their body.

The focus should be on putting supportive structures in place across all areas of life — structures that reduce pressure, support regulation, and build a foundation of safety and trust around food and bodily cues.

Key supports to prioritise:

Felt Safety:

Cultivate a genuine sense of internal and external safety. This includes offering safe foods without pressure, keeping the eating environment calm and predictable, and ensuring sensory needs are respected. When the body feels safe, it can more easily notice and respond to hunger cues.

Predictability:

Provide consistency and clarity around food, routines, and expectations. Predictability doesn’t have to be rigid; it simply reduces uncertainty. When a PDAer knows what’s coming, they can mentally prepare, regulate, and make choices within that structure — all of which help maintain autonomy.

Autonomy:

Support choice and control in any decisions that involve the PDAer. Autonomy reduces threat and lowers demand, making it easier for the nervous system to stay regulated. Even small choices (what plate, where to sit, what order to eat in) can make a meaningful difference.

Flexibility:

Be prepared to adapt to needs in the moment without pressure, correction, or rigid expectations. Flexibility signals safety — it shows the PDAer that their needs will be met without conflict or coercion. This creates space for trust and coregulation.

Written by Margo White, your Melbourne-based neurodiversity affirming clinical nutritionist and Neurodivergent advocate.

This article is intended as general advice only and does not replace medical advice. It is recommended that you seek personalised advice specific to your individual needs.

Infographic created by Margo White copywrite © 2025